Research Tips by Dr Julian Quinn

Here, we outline some general pointers to writing a short document for seeking funding or some other type of support.

Decide what the proposal is about and distil it into a short title

This is a useful way to refine the central idea in a proposal. It must be clear to you if it stands any hope of being understood by the reviewer or audience, and title brevity and clarity has impact.

Be mindful of who will review it

Any proposal must be tailored to its audience and their interests, but this is easily forgotten. The most difficult type of proposal is that intended for a lay reader. After a long training in a highly professional and technical environment it is extraordinarily difficult to write in lay language without jargon and in easily understood concepts. Practice and feedback from others is usually the only way.

If it is short it must be highly structured

Do not waste any space with rambling text. Make sure any text is really needed, so upon reviewing it delete any text that does not enhance or further the proposal. Try starting with a set of dot points for each section then turn it into prose. Use references to minimise unnecessary methods detail.

Proposal overall structure

This should generally resemble the following: short preamble, briefly stated aims, introduction or context to the work, methods and approaches, details of proposed work (which may be divided into sections), and outcome significance. The work detail sections should usually include a brief rationale (why you need to do something), the detail (what will be done) and expected outcomes.

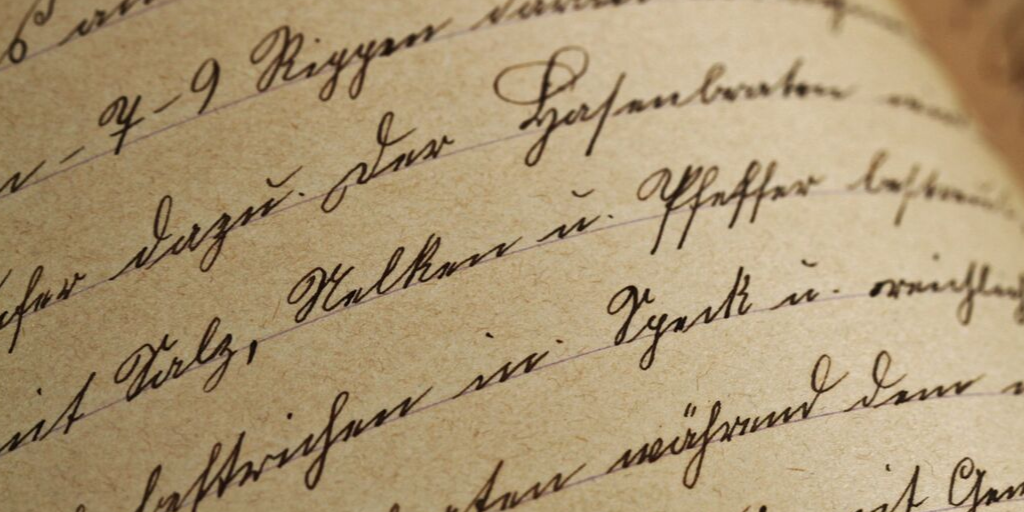

Use diagrams, flow charts and illustrative images where possible

1 picture = 1,000 words.

Textual flow

The language should be clear with linkage between ideas and a good style that leads gracefully and logically from one point to the next. This is a skill garnered over time through reading, writing and critiques. The style and vocabulary typical for the field should be used since otherwise becomes an irritating distraction for the reader/reviewer. Those conventions evolved for a reason.

Writing a short document is hard

Short documents are always harder than long ones because shortage of space means a document needs to be very carefully structured, which is a surprisingly hard thing to achieve. It involves stripping the document of non-essential detail and ordering concepts to flow easily. Often a good approach is to make a solid attempt (which will be too long), then abandon it for a while, then upon return obvious cuts and unnecessary frippery is evident. If the document size goal is not reached and not yet visible, repeat the cycles of abandonment and return and eventually it will get there.

If there are project submission guidelines, read them carefully and adhere to them.

Usually for short submissions the most important feature is length of the proposal or proposal section fields. Like all the guidelines these should be respected in every detail or its submission may not be accepted.

The first section or page is the most important

This is where 90% of the impact is made. Any reviewer will be impressed by an opening that has a short, cogent summary of the subject, especially if it uses flowing English and links important concepts clearly to make a compelling case. Do not use grandiose styles but try to sound interesting and creative where possible, though this is often a hard ask. The ideal is to entertain or at least revive the poor tired reviewer, as their job is very tough and they may have read 50 proposals before yours.

Don’t be boring

Break up text, make it visually interesting, and use diagrams and pictures where possible. There is nothing worse for a reviewer than pages of dense, poorly written prose. Use bold and italic fonts sparingly. Keep sentences below 3 lines. Use short paragraphs with linked ideas and link paragraphs to keep the flow. If possible, break up text with short, cogent titles that not only help comprehension but look good on the page. Sound precise and slightly fussy in detail (especially method descriptions, if there is the space) without being long-winded.

Don’t be repetitive

If you said it before, why say again? Especially avoid saying it again with the same form of words, which always looks incompetent. There again, the major concepts and important points may have to be restated in different forms in different sections of the proposal, but vary the choice of phrasing.

Get someone to read your proposal critically

For all but the most trivial project this is absolutely crucial. You need the objectivity that a disinterested reader can bring and you need constructive criticism even if you are already a good writer. All statements in a proposal need to be examined from a range of perspectives, flow of the arguments and the language both need to be checked.

Do not be precious about your work when receiving criticism.

Take criticism about your writing very seriously and consider it as a gift even if it is a gift you don’t like. What is better – having flaws pointed out by a colleague or by your proposal reviewer? Always remember the point why the proposal is being written – you want the reviewer to give you something significant such as grant funding.

Make the expected outcomes/conclusions look different to the aims.

It is so easy to make the outcomes (which should usually be placed at the end of each proposal section) look the same as the aims, which after all is logical. But don’t do it. Try putting outcomes in a wider context and make them more discursive than the Aims. The same problem can occur with aims and conclusions

Does the whole proposal look simple?

Simple good, complicated bad.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.